AT&T’s Bellboy pager at the Seattle World's Fair, 1962. pic.twitter.com/P86fQLQUfC

— Humanoid History (@HumanoidHistory) July 9, 2021

From the Seattle World´s Fair, 1962.

Technology, you´ve never let us down!

Tales of True Adventure for Rugged Men Not Unlike Yourself

AT&T’s Bellboy pager at the Seattle World's Fair, 1962. pic.twitter.com/P86fQLQUfC

— Humanoid History (@HumanoidHistory) July 9, 2021

From the Seattle World´s Fair, 1962.

Technology, you´ve never let us down!

Oscar-nominated animated short from 1966. Anybody seen it before? Seems like I have, but who the hell knows anymore.

Clear, precise instruction!

How platforms decay, as explained by Cory Doctorow to NPR. Finally a name for what we may not consciously recognize but deep down know is going on.

… I think Facebook’s a good example. Facebook went through the whole lifecycle of platform decay. They started off by offering a really good deal to their end users. They said, “Hey, leave MySpace, come to Facebook. It’s just like MySpace, except we only show you the things that you asked to see, and we’ll never spy on you.”

And then once those users were locked in — because once you’re in a place with all of your friends, it’s really hard to leave — they started to take away some of that good stuff they gave them, and they handed it to advertisers and publishers.

To the advertisers, they said, “We were lying when we said we weren’t going to spy on these guys. We’re totally spying on them. Here’s all the data you need to target them for ads that we’re not going to charge you much money for.”

And to the publishers, they said, “We are also lying when we said we’d only show them the stuff they asked to see.”

And then once the publishers and the advertisers were locked in, well, they took away those surpluses. The ads got more expensive. Publishers had to put more and more of their content — not just to get recommended, but even to be shown to the people who subscribed them. And that’s the final stage, the stage where there’s just only the residual value left on the platform that the platform owner thinks will keep the users and the business customers they bring in stuck to the platform. And that’s when we’re at the beginning of the end.

Further reading.

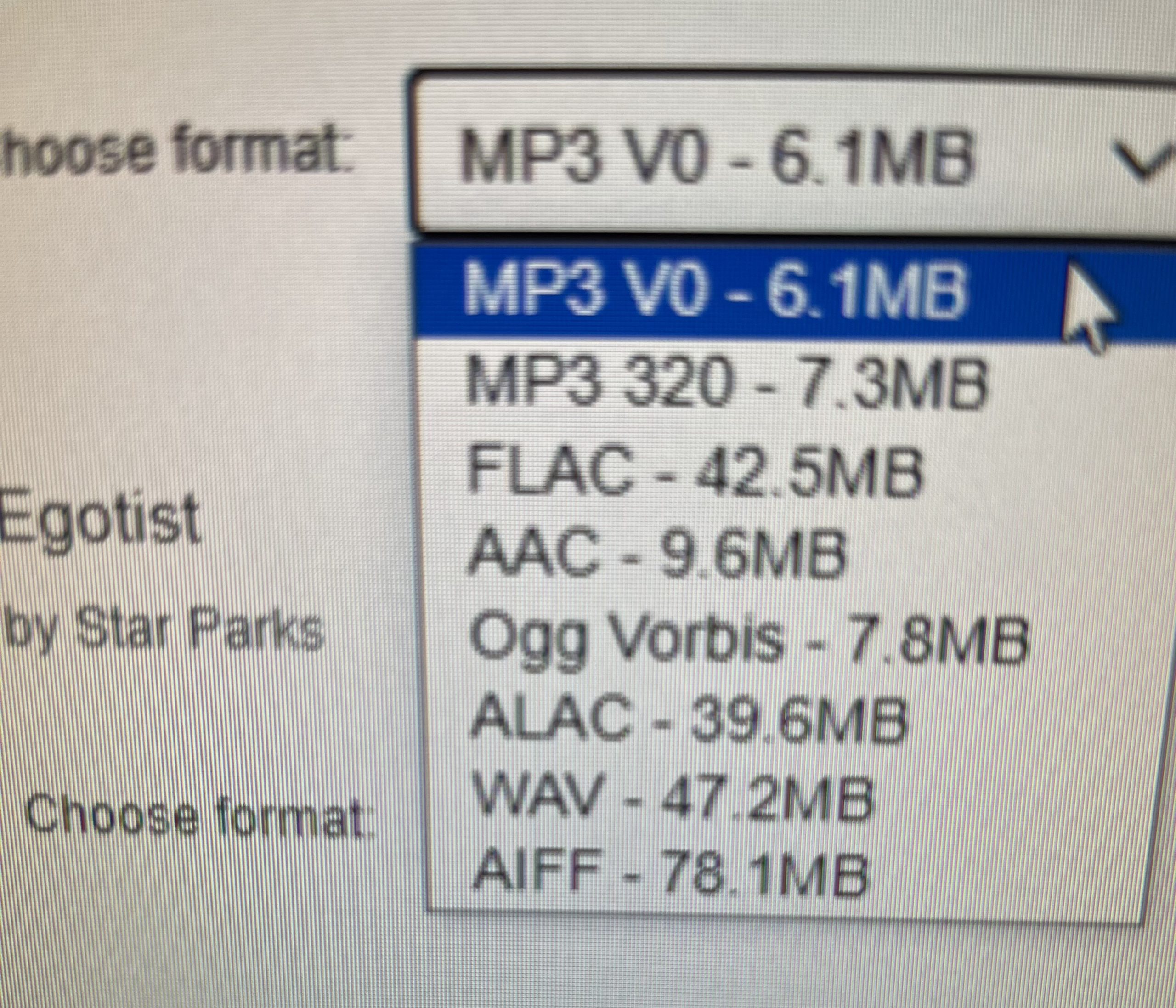

While downloading a pleasant tune from the Bandcamp recently, I was offered this stunning array of options. I stayed with my mp3 because I like overly compressed crap.

Those of you who recently released albums, did you offer the FLACs and the AIFFs? Those cowbells really pop in AIFF!

[compiled from multiple sources]

Dolby Atmos technology allows up to 128 audio tracks plus associated spatial audio description metadata, which includes sound type, location, movement, intensity, speed and volume.

One of the reasons other highly touted surround sound technologies like 5.1 and 7.1 failed to catch on is because they required a specific speaker configuration. Dolby Atmos, however, is scalable and can adapt to a variety of setups.

The first Dolby Atmos installation was in the El Capitan Theater in Los Angeles for the premiere of Brave in June 2012. As of October 2022, there were over 10,000 Dolby Atmos enabled cinema screens installed or committed to.

Dolby Atmos has also been adapted to a home theater format and is the audio component of Dolby Cinema. Most electronic devices since 2016, as well as smartphones after 2017, have been enabled for Dolby Atmos recording and mixing. Apple has emphasized playback on its AirPods and Beats Fit Pro devices, which all offer a version of the Atmos experience with dynamic head tracking (where the sound shifts along with a user’s movement) in the $200 to $500 range.

“In general, you have to try to put the tracks into a speaker array so it doesn’t sound too jarring or gimmicky,” a sound engineer said. “The goal is to feel like you’re sitting amongst these musicians as they’re performing. Like all mixing, it’s subjective, and how you approach it really depends on the music itself.”

Susan Rogers, a longtime engineer for Prince, was invited to Dolby company headquarters in San Francisco to listen to a new Atmos mix of Prince’s “When Doves Cry,” a track she originally worked on. She observed that music is a potent form of communication in large part because the consummatory phase happens entirely in the listener’s head. Having clearer and more sound sources can actually make it harder to know what to pay attention to. “That was what I noticed listening to ‘When Doves Cry’ in Atmos,” Rogers said. “It sounded amazing, but it was more difficult to assemble it into a unified whole in that private place I listen to music. I found it distracting.” Her “knee-jerk reaction was ‘do not want,’” she said. “But over time I may learn to like it.”

Any of you esteemed audiophiles care to weigh in? Anyone tried it out?

2,000, in fact.

But the trailer sure is fun. President Tom Arnold?

Just what you need on your feet when you stumble out of an ale house.