I´m so down for this. Great article here.

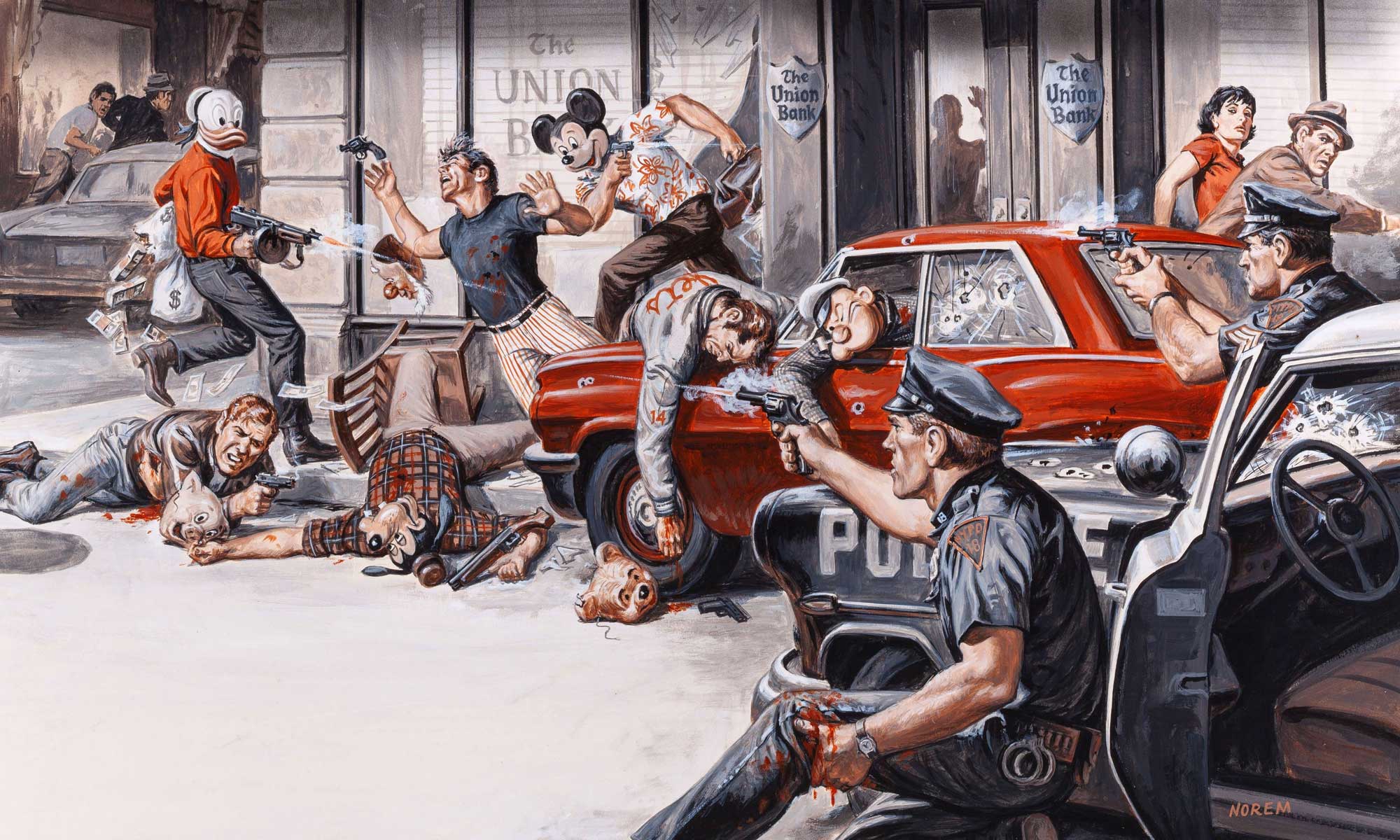

Tales of True Adventure for Rugged Men Not Unlike Yourself

“Pure Gremlin.”

A Murder at the End of the World was superb.

Fargo is excellent.

I’m one episode into True Detective: Night Country. It seems can’t miss.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnPl4PuNb5U

Can’t resist that beat. Or walkin’ around like these fools.

Relentless and obsessed.

And a bit shady!

John Groves, born in Hamburg to English parents.

I came to appreciate his genius when a vintage Mentos commercial recently appeared on one of my devices.

At the time it came out (1992) I had the same reaction as everyone, i.e.

WHAT FRESH HELL IS THIS. But this being in the before times, prior to Makerbot inventing the internets, I had to simply wonder how the abomination arose, and wallow in ignorance.

But now…

Enter Bastard Research Division.

The candies, in various formats, have been around since the 1930’s, and are owned by the Perfetti Van Melle, an Italian-Dutch corporation. Van Melle hired the ad agency Pahnke & Partners out of Hamburg, to come up with the ad spots. Groves composed the theme, which is available in extended format!!

The bulk of commercials were shot in South Africa, and aimed squarely at the US and Canada.

Viewers who spotted the ads when they premiered in July 1992 were driven to distraction by one intangible: The ads seemed disconnected from actual human behavior, and the song itself was critiqued for appearing to be an English translation that didn’t get the lyrics quite right.

When Van Melle was asked “what the actual fuck?” they responded coyly, realizing they had a phenomenon on their hands. The less they answered, the more interest there was. Sales went from $20M in 1991 to $140M in 1996, worldwide. In the late 90’s, Altoids caught fire and were blamed for a decrease in Mentos market share.

The singer is allegedly Richard Ryan Graves (aka Frank Ryan), who takes zero credit for it on wikipedia or elsewhere. He was in Hamburg at the time, so he remains a likely suspect.

I’ve been enjoying this series recently.

To say Cunk is an idiot is an insult to idiots—this is a person who stone-facedly inquires whether the pyramids were built from the top down. She calls the academics she speaks to “clevernauts” and “expertists” and then proceeds to ask these befuddled “boffins” about anal bleaching in ancient Rome. In between, she characterizes the advent of farming as a product of lazy hunters, math as a “tragic invention,” sports as “theater for stupid people,” the Model T as a “truly terrible car” and missionaries as “God’s bitches.” With her pop culture knowledge far outstripping her knowledge of literally anything else, she at least nails the name of the 5-part series’ religious episode: “Faith/Off.” Through all of it—even through the show’s inexplicable “Pump Up the Jam” leitmotif—Morgan never breaks. This is stupidity at its deadest seriousness.

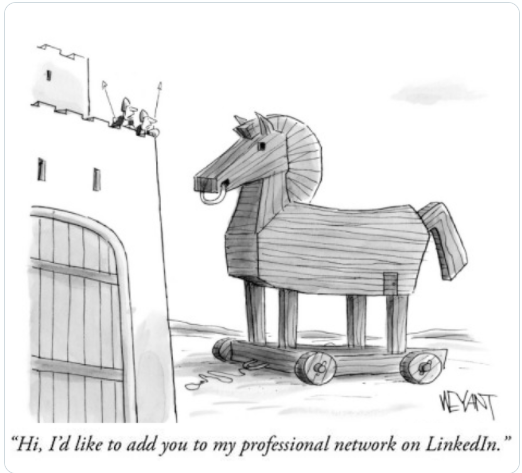

In 2006, a blogger argued that the above caption worked for every New Yorker cartoon. As I am not as highbrow as you lot, I wouldn’t necessarily know.

More recently, the following universal caption has been suggested:

I’ll leave it to all y’all to decide if they both work for every cartoon.

Has anyone entered this week’s caption contest?