You’ve all heard, but there has to be a shrine here. There was nothing quite like the Stones firing on all cylinders. The Faces tried, but couldn’t entirely replicate it. Some of that mojo came from Charlie. As much a musician as a drummer, I’d pick him over thousands who might be technically better.

We´re at the hotel and Mick says ¨Right are you coming out to eat?¨ and I say ¨No

I´m in the middle of folding my pajamas¨ and he says ¨Haven´t you done that yet?¨ because he never touches a bloody thing. Mick´s got a valet, three or four people. I could have that, but I bloody hate it. Nobody touches my clothes.

His style was so uncomplicated it was easy to miss what he was doing. Easy for me to miss, anyway.

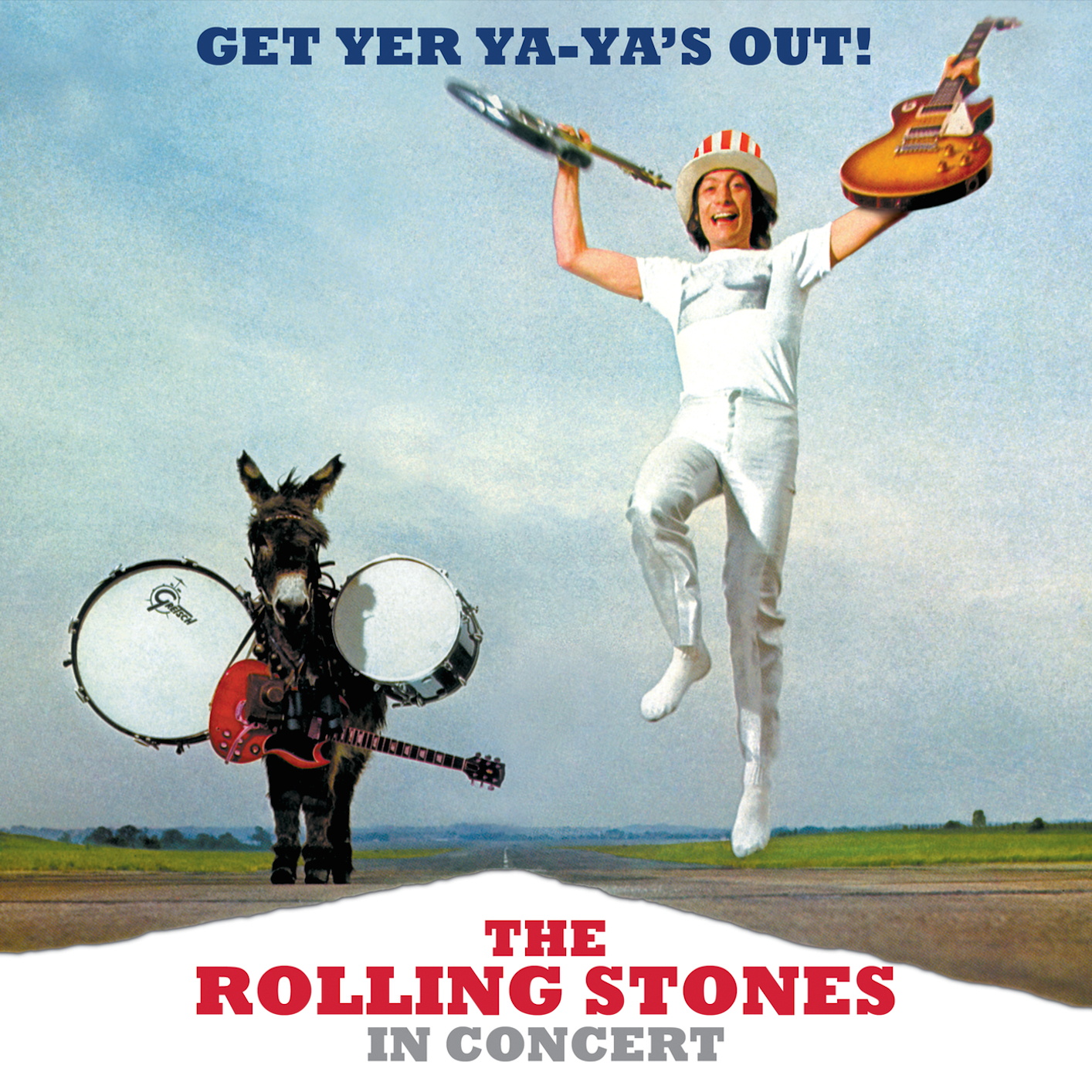

From Charlie Watts, The Unlikely Soul of the Rolling Stones

His distinctive drumming style — playing with a minimum of motion, often slightly behind the beat — gave the group’s sound a barely perceptible but inimitable rhythmic drag. Bill Wyman, the Stones’ longtime bassist, described that as a byproduct of the group’s unusual chemistry. While in most rock bands the guitarist follows the lead of the drummer, the Stones flipped that relationship — Richards, the guitarist, led the attack, with Watts (and all others) following along.

“It’s probably a matter of personality,” Wyman was quoted as saying in Victor Bockris’s book “Keith Richards: The Biography.” “Keith is a very confident and stubborn player. Immediately you’ve got something like a hundredth-of-a-second delay between the guitar and Charlie’s lovely drumming, and that will change the sound completely. That’s why people find it hard to copy us.”

Watts’s technique involved idiosyncratic use of the hi-hat, the sandwiched cymbals that rock drummers usually whomp with metronomic regularity. Watts tended to pull his right hand away on the upbeat, giving his left a clear path to the snare drum — lending the beat a strong but slightly off-kilter momentum.

Even Watts was not sure where he picked up that quirk. He may have gotten it from his friend Jim Keltner, one of rock’s most well-traveled studio drummers. But the move became a Watts signature, and musicians marveled at his hi-hat choreography. “It’ll give you a heart arrhythmia if you look at it,” Richards wrote.

To Watts, it was just an efficient way to land a hard hit on the snare.

“I was never conscious I did it,” he said in a 2018 video interview. “I think the reason I did it is to get the hand out of the way to do a bigger backbeat.”

The greats are barely aware what they do, they just do it. It’s left to colleagues, other greats, or “experts” (usually failed musicians) to analyze and explain.